THE IRON WORKS - THE BEGINNING OF IRON TOWN

RICHES IN THE WILDERNESS

There was treasure waiting at Marmora. It lay covered by the silent forest. It lay twisted and trapped in the hard precambrian rock. But it was there. There were clues, where the ice and water had washed the rock face clean. The tell-tale streaks of red were unmistakable. The treasure was iron - magnetite ore formed in the earth's molten crust untold millions of years ago. At Marmora the ore was plentiful, and near enough to the surface to be mined. Nature had blessed Marmora with a magnificent river winding through limestone shelves. Not far away, the precambrian rock touches a corner of Crowe Lake. Within it bosom, that rock held an immense and extraordinary formation. It was a mountain of iron-rich ore, the likes of which the pioneers had never seen. By the closing decades of the 18th century, surveyors and settlers were pushing up .into the headwaters of the Trent and Crowe Rivers. Government authorities were getting exciting, if sketchy, reports of the riches at Marmora.

IRON FOR THE WHEELS OF PROGRESS

Our industrial age awoke with a hunger for iron, and for the technology to forge the shafts, gears and wheels of progress. Agriculture, milling, manufacturing, building, cooking, transportation - nothing was possible without iron. Like oil today, it was the dark root of progress and power. The colonial administration saw the need to develop an iron industry in the Canadas. Supplies from Europe and America were costly - and, as the war of 1812 had shown, of doubtful security. The forges at Ste. Maurice, below Montreal, faced exhausted ore supplies. Thus, Sir Peregrine Maitiand, the Lieutenant Governor, canvassed interest in the business community in undertaking iron works where ore and available water power could be found. Substantial military supply contracts were hinted at. Land grants to aid the entrepreneur could be arranged. In 1819, Charles Hayes, a man equally of vision and wealth, visited Maitiand to discuss a possible iron works venture.

ENTER CHARLES HAYES (1751-1844)

Hayes had made his fortune in the London business community. His remarkable organizing ability and drive were able to guide his entry into the opening field of iron making. In 1820 he emigrated to Canada, settling near the Trent River just a few miles west of Stirling. Undaunted by the wilderness - the nearest spot of civilization, at Kingston, was a hundred miles away - Hayes carved a road through to Marmora. He then began the simultaneous construction of a mine, mill and smelter operation, plus the erection of homes and community buildings to house the workforce. Quickly exhausting the available ore at Marmora, he opened up mining operations nearby at Blairton, securing grants to the land in return for surveying the area.

Arthur D. Dunn, an Industrial historian and archaeologist from Ottawa, wrote of Hayes:

Sketch by Susanna Moodie - Marmora Mine

"In 1820, Charles Hayes, a businessman from Dublin, Ireland started to construct a road north from the Trent River at the present location of Stirling, to the falls on the Marmora River, now the Crowe River, in order to construct an Iron Works at that point to manufacture cast iron and wrought iron bar for the needs of the now rapidly growing population of Upper Canada.

During the first year he lived on the Trent River,probably near Stirling,while the road was cut and the first buildings erected at the new village of Marmora. By 1821 probably a number of houses had been constructed, including one for Charles Hayes and his wife, and it is possible that by that time the first saw mill had been erected and was in use to provide the lumber for the construction

of the buildings that were to follow.

By the time that the year 1824 had arrived, the year the attached map was produced, the village had became a fully integrated iron working community, and had facilities for the production of flour from wheat produced on the 150 acre farm located, it is believed, where Madoc is today, leather in the tannery largely for the conversions into aprons and other protective clothing for the workers, and of course the furnaces and forge to manufacture the cast and wrought products that it had been developed to produce."

WILDERNESS COMMUNITY

It was as if nature had designed a patch of this earth ready made for an Ironmaster. The ore was set at Blairton, the waterpower five miles away at Marmora. They were joined by a calm waterway ideal for navigation. Along the sides of the lower part of the waterway was the limestone needed as a flux in reducing the iron ore. The limestone

ledges overshadowed the river below and stood as a natural loading ramp to the top of the furnaces Hayes would build. All along the shores and back up the Crowe River system timber awaited the lumbermen and its trip to be reduced to charcoal for the furnaces.

The only thing forgotten was the people to buy the products. The mountain of ore would be discovered to be two 'lenses' of sulphur-free ore and over half a century 300,000 tons would be mined. Charles Hayes' barges would navigate the Crowe with ease. His furnaces would 'campaign' successfully in continuous blasts which would last up to six months, four hours a day. The river would drive the waterwheels and the waterwheels would pump the bellows, and out of the base of the great furnaces would pour the molten'iron to be transformed to ballast,

pots, stoves and even cannons.

By 1822 Hayes had constructed an almost self-sufficient community of 200 people. He built a sawmill and grist mill beside the Marmora waterfalls. A bark mill ground up waste bark for the tannery, which then provided protective clothing for the miners. Almost thirty houses were built, plus a school, and buildings for the forge and mill operations. These in turn included three coal houses capable of storing two hundred thousand bushels of charcoal. There were carpenter and blacksmith shops, wood turning and pattern making shops, plus barns, sheds and a piggery. A community farm lay some distance towards Madoc. A bake house, dry goods and provisions store completed the settlement.

Last firing of Pig Iron at Marmora Iron works

FROM FURNACE TO IRON FACTORY

At the fiery heart of the Marmora operation were two great furnaces, having interior diameters of 8-1/2 and 9feet. Air to the one was provided by a paired German bellows, each bellow measuring 28' long by 15' wide. The second cylinder used a three cylinder blowing engine, each 5'7" cylinder having a 3-1/2" stroke.

Because the two furnaces faced each other, their output could be combined in heavy casting operations. When casting was not underway, the furnaces turned out "pig" iron. This was either shipped as ballast to the naval depot at Kingston, or it was used on site to make "wrought" iron. In this process, the "pig" was remelted in a smaller "finery" furnace, somewhat resembling a blacksmith's hearth. The resulting "bloom" was pounded by a massive water-driven hammer to squeeze out impurities.

Reheating in the final "chauffery" furnace, and further hammering, drew the bar out in a pure enough form for sale for further manufacturing operations.All this equipment was driven by some twelve water wheels. The wheels for the main furnace blowing engines were 25 feet or more in diameter, and 6 to 7 feet wide.

A BUSINESS IN JEOPARDY

Although he was Upper Canada's leading industrialist, Charles Hayes could not get his way with the masters of the colony. The Family Compact as they became known valued the Ironworks but had little need for the individual Ironmaster who had built them. If Hayes packed his bags and left for England he could hardly put his furnaces in them. Perhaps a change of management would not be such a bad thing.

The grand plans for joining Crowe Lake by canal to Lake Ontario departed with Hayes' departure. From 1825 to their complete abandonment in 1873, the Ironworks went through a series of less inspired ownerships. The dream of Marmora as the heart of a new industrial province faded.

For its time, the Marmora works were the most advanced iron works in Canada. Secure in ore supplies, water power and the vast amounts of hardwood charcoal to fuel the furnaces, the future looked assured. Yet the operation was running into serious trouble. Transportation and road maintenance costs became crippling. The governing authorities did not provide the volume of orders originally and encouragingly hinted at. It was difficult to keep the business fueled with capital, although Peter McGill, the emergent financier of Montreal, was prepared to advance some loans. Hayes and his family returned to the capital markets of England in an attempt to find a more substantial and secure underwriting. The times were bad, however. Business activity was slack. The British government was unresponsive, and bankers were unwilling to advance money based on Hayes' other holdings. Discouraged, Charles Hayes moved to Dublin, where from 1839 to his death in 1844, he rebuilt his earlier fortune while dreaming of a return to the Marmora Iron Works.

OBJECTS OF IRON FOUND NEAR THE SITE OF THE FURNACES

Arthur Dunn raises a good question: Where did the equipment come from?

"Hayes no doubt, had expert advice on the setting up of his works from unknown expertsin England before coming to Upper Canada in 1820, and undoubtedly had the capable assistanceof excellent millwrights to construct the buildings, furnaces, and the various pieces of equipment that were required. Evidence is shown in the details of some of the equipment installed. Where this equipment was purchased is unknown.Were they purchased from England? If they were, then who agreed that the equipment could be shipped out of England, as the law at that time made specific provision for the non-exportation of equipment for making iron products out of England, and even more specifically precluded the movement of those skilled in the manufacture of iron products to the Colonies. But in some way Hayes had managed to get around these regulations and had even planned to install a rolling mill- a relatively modern innovation."

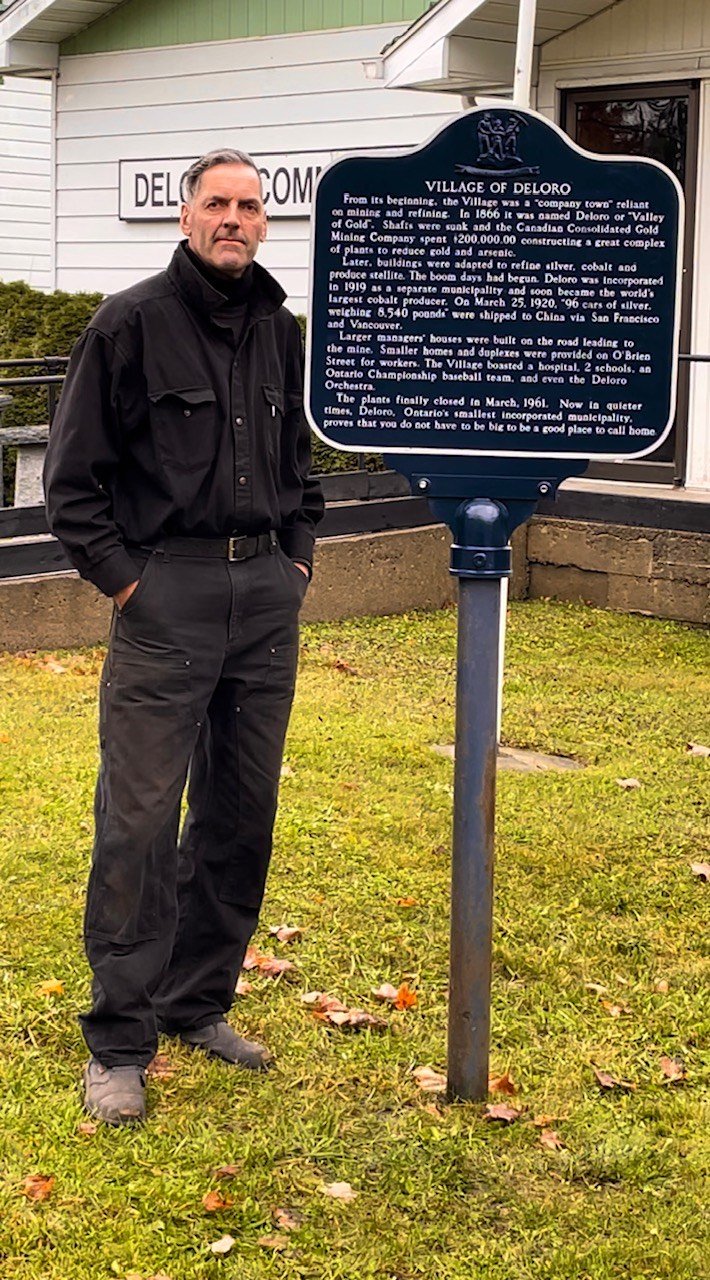

1997

ONTARIO HERITAGE FOUNDATION PLAQUE

In the late 60's, the Ontario Heritage Foundation presented Marmora with a Provincial plaque marking the site of the Marmora Iron Works of 1823. Here we see the formal unveiling, which unfortunately was in the wrong location, beside the Crowe River bridge. It was later moved by the Marmora Historical Foundation to the rightful place, near the Municipal pump house, just south of the east end of the dam. ***

Mrs. helen Meiklejohn, clerk-treasurer Wm Shannon, bill Mac Donald, Ontario Rep, Ontario Rep, Mayor of Belleville, Dr. Russell Scott reeve /or warden Mr john Wilkes, M.P.P.clarke Rollins , unknown , far right Ed O’Connor

Ed O’Connor had the honour of unveiling

The corrected location, now the site of the municipal pump house and garage.

*** The plaque was inadvertently knocked down and still awaits being reinstalled. It is stored in the pump house.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGS

1978, 1980 1982, 1984 AND 2005

BY PATRICK REDICAN 1980 The more Arthur Dunn digs, the closer the Marmora of 1980 comes to the Marmora of 1820. And the closer the Marmora of 1820 comes, the closer we come to a tourist goldmine - or so some of the visionary members of the tiny, determined and rather successful Marmora Historical Foundation believe..

Of course it all hinges on Mr. Dunn's digging, but then, that's a good place for it to hinge. Mr. Dunn, a retired engineer, is a digger with equal, tireless, enthusiastic, thorough - and with quite a record of success.

1980

Usually his digging involves searching through old records and documents for leads into other old records and documents that might finally turn up facts and figures about the ever widening field of his fascination - the history of iron- But this summer he was involved in digging of a more physical sort - .unearthing the foundations of the number two blast furnace built in 1820 for the Marmora iron works. And once again he was successful.

With three local students Rick Empey, John Wilson and Rosemary Viljanen - providing the backwork, help from other members of the Marmora Historical Foundation, and financing from both the municipal and federal governments, Mr. Dunn managed to uncover most of the foundation and a few other interesting things as well, in two short months. A dig at the site of the old Marmora Iron Works uncovered the foundation of the number two blast furnace and has provided the Marmora Historical Foundation and iron historian Arthur Dunn with a lot of information on how the furnace operated.

The dig was carried on over the summer by three students working under a federal Young Canada Works project grant. Mr. Dunn commuted from Ottawa on a regular basis to oversee the excavation. Basically the students dug out the limestone floor of the furnaces, the pipes used to drain it and the troughs where the two 27 foot waterwheels which powered the furnace were placed. They have also located a set of stairs leading up the cliff or rock ledge which the furnace abutted and what appears to have been the spot where the ore, limestone and charcoal were dumped in from above. Pieces of iron which will be taken for analysis plus two large "bears" or chunks of iron left in the furnace when they used it for the last time were also found.

The furnace was constructed in 1820 and was set off and on until the turn of the century ,when it was torn down entirely to make way for the rail line along the river to Cordova. Mr. Dunn conducted a tour of the site of the dig and the whole area in which the iron works operated for members of both councils just before the students filled in the dig last Friday. The results of the dig were not made public until after it had been filled in because Historic Foundation officials were afraid of accidental damage or vandalism if the public had too free access to the area.

The uncovering of the foundation of the furnace, believed to have been made of limestone and lined with brick inside, has raised as many questions as it has answered. Mr. Dunn said that the construction of the troughs for the waterwheels, for instance, has allowed him to be able to identify just what type of waterwheel was used. On the other hand, the engine that they powered - "a three cylinder monster with pistons five feet seven and a half inches long and three foot three inch stroke" - are still the source of puzzlement.

"We don't know where they came from. The United States didn't have the facilities to make something this big and in Britain they were still using two or four cylinder engines. Perhaps they came from Sweden. We just don't know yet." Mr. Dunn said that, although there was a ban on the export of such heavy machinery from Britain at that time, their presence at the Marmora Iron Works does not necessarily mean they were smuggled in.

"It's very likely that the original owner, Charles Hayes, made some sort of a special arrangement with the government to bring this machinery in. We know he was supposed to have had government assistance on this project at one .time, and, although that never came through, we can presume this sort of cooperation was also possible," Mr. Dunn said.

One of the remarkable things about the site was the fact that piping laid in 1820 was still in good condition when uncovered. Mr. Dunn attributed this to the high quality of the material used and the highly alkaline nature of the water because it ran through limestone. Further excavation is expected to receive government funding over the next few years and the historical foundation hopes this will be the beginning of a museum. Most of what has been uncovered has been covered over again and so there isn't much to see now. But even when it was all uncovered, there wasn't much to .see. Until, that is, Mr. Dunn started talking about It.

Then instead of a few stones, pipes and ditches, you could almost see the furnace smoking away (preesuming of course, the thing did smoke). Listening to the morass of detail he can extract from unearthing the channel where the water wheel turned or the original blast pipe, still in working shape, it's almost mind-boggling - a problem of too much information and not knowing how to use it.

Slowly though , a picture begins to form. Most striking is the fact that in 1820, in the middle of nowhere, a man, or a group of men, was able to establish what was then a very technologically advanced iron works, in spite of enormous restrictions. Much of the machinery used, as well as the skilled tradesmen needed to operate them, had to have come either illegally or by specialround about arrangement. In 1820 Britain, hoping to keep her colonies as underdeveloped sources of raw materials and consumer markets for her manufactured goods, banned export of both these things, as well as not allowing manufacturing in her colonies.

It's a story of pioneer effort that rivals those with which we are more familiar - clearing land, lumbering - and yet, because it has .to do with technology and industry. it has until this time, been overlooked. "

"What we have here," said Mr. Dunn, probably for. the thousandth time, since he'll tell anyone who will listen, "is one of the most up-to-date for its time, the largest, the most complete and the most self-contained iron works in Canada. It's something that the more we learn about it, the more fascinating it becomes. We know now for instance that in setting up the bellows for the furnace they used a very unusual method that hadn't been seen anywhere before. We know that they used three pistons, not the usual two or four to fire the furnace. We know what kind of a waterwheel they used ... "

Water filtration plant expansion hits a snag

By Nancy Perrer (2005) - Marmora - Last week, work began in earnest by Nick Gromoff, Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation, Kingston, on the site of the water filtration plant proposed expansion. Engineering firm Greer Galloway recommended, last fall, that to meet Ministry of Environment requirements, the water treatment plant be enlarged by constructing an addition at the rear of the current building.

However, the land on which the plant sits has an historical designation so Gromoff was on site Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday of last week doing Stage 1and 2 of "the archaeological process; Stage 1 is the historical background and assessing the archaeological potential of the site. "That's when you do archaeological background and assess the topography and basically make your best judgement on whether there will be sites there," Gromoff explained. "In this case, we used the previous archaeology that had taken place."

Gromoff pointed out a square sand patch in that wall. "That is the end of a wall discovered when a previous trench was dug in 1984." The location of the north and south furnaces of the original ironworks was identified, based on an historical map. Gromoff, using the previous archaeological data and historical maps, predicted where they would find the wall.

"So here we are. We found the wall. That's Stage 2. There is a site. Now what we are trying to do is find this other wall." Gromoff pointed out that the original sketch was the previous archaeologists interpretation; he might have been wrong; the wall might actually have been the outer wall of the wheel house. "That's what we're trying to find out in Stage 2. If we don't find it in the next two days, we'll still be coming back to look for it but w're going to have to wait until the water drops in the river. "We're by no means done here". Gromoff concluded. Stage 3 involves defining the liits of the site. But, he said, what he will probably do is jump straight to Stage 4, which is full excavation.

"My first recommendation will be to avoid the (excavated) wall; re-design the (water filtration) building so it doesn't impact it at all. If they can't do that, and the Ministry of Culture says OK, then we will archaeologically excavate that wall to bedrock by hand, but the groundwater has to come down a lot."

The process would be to excavate the strata beside the wall and then totally photograph and record the wall, measure it in place, and then remove the rocks If they can't re-design the water filtration plant expansion. In explanation, Gromoff noted that, when subdivisions go in around Toronto, archeologists remove entire Indian villages, every day. This is no different, he said: The 'rocks' would be given to the municipality and they could do what they wanted to with them.

Hmmmmm....WONDER WHAT HAPPENED TO THE ROCKS?

While the municipality is Cataraquis' client, it has a loyalty to archeological resources and he has responsibility to the Ministry of Culture, which predicted what Gromoff would find.

"Thats why Chris Andersen, regional archaeologist Ministry ofCulture, insisted that archeology be done here the first place," Gromoff explained "He was totally expecting that we would find that wall and it is pretty well exactly where it should be."

Gromoff will send a report to the Ministry of Culture, Greer Galloway and the municipality. After the Ministry reviews the report, it will approve the type of further work to be done. Marmora and Lake Council will have to wait a little longer to know the fate of its water treatment plant expansion

(The water filtration plant was expanded and a garage built on the site not long after, without a snag.)