NO PLACE FOR MERCY - Murder in the backwoods

/Marmora’s first and well-known Catholic Priest was Father Michael Brennan. He started preaching in the mid-1820s, at St. Matilda’s, the little stone church on the west side of the Crowe River, north of the dam. He travelled, usually by horseback, through the diocese. He performed his first baptism on October 17th, 1829 and his last on October 11th, 1869, twenty days before he died. For the forty intervening years he showed total devotion to his responsibilities and his people. His funeral parade was followed by 500 parishioners through the streets of Trenton. Shops were closed as a token of his universal respect.

St. Matilda's, Marmora,

One of the good Father’s most trying duties arose in his mid-sixties; he had to do all that was possible for a young couple accused of a murder that had occurred far back in the County of Hastings.

Richard and Mary Aylward had taken advantage of a land grant for property which would be free to them if they cleared a field, and built a log home in which they would live. When the Aylwards arrived at their property, in 1862, they found an older neighbouring couple with a grown son, the Munros, living almost directly across the road. At first, as they settled in, relations while not friendly, were at least acceptable.

Richard even sold a few of the chickens he had brought up to the property, to the Munros. From there things were destined to go swiftly downhill. Having sold the chickens, Richard, and more so his wife Mary, felt that the chickens should, so to speak, no longer cross the road. Whatever the reason.

Perhaps remembering the joys of their former home, the hens crossed back and showed up where they came from to gobble the Aylward chickens’ grain. The Aylwards took these visitations enormously seriously. Neighbour Munro and his son thought that the complaint was petty, and would not build a fence nor do anything to stop their chickens from trespassing.

Things swirled down from there. Before long there was a loud confrontation on the Aylwards’ property; a scuffle began, and Richard and the Munros were at blows. Richard had been holding a shotgun, that he had filled with buckshot, he said, to lay the chickens, and the dispute, to rest. The shotgun went off and the Munro’s son was shot, but not seriously, in his back. After having had numerous pellets removed, he seemed none the worse for wear.

The elder Mr. Munro was not the sort to back down, but nor was Mary Aylward. As Munroe continued to confront Mary’s husband, she grabbed a scythe and swung at Munro, intending, she later admitted, ‘to cut off his head’. She took a second swing. Both connected but Munro was nevertheless able to hobble home. There being no competent medical care anywhere nearby, he enlisted the help of an ‘Indian Medicine man’. Despite this he died twelve days later.

Up in the backwoods, it took weeks for the news to spread to the authorities seventy miles away in Belleville. A Constable was sent up for a two-day trip by horseback. He was to investigate and, if charges were warranted, to bring down those he determined to be responsible. He found that both the wife who did the deed, and her husband, as titular head of the family, should at least face the next available Judge.

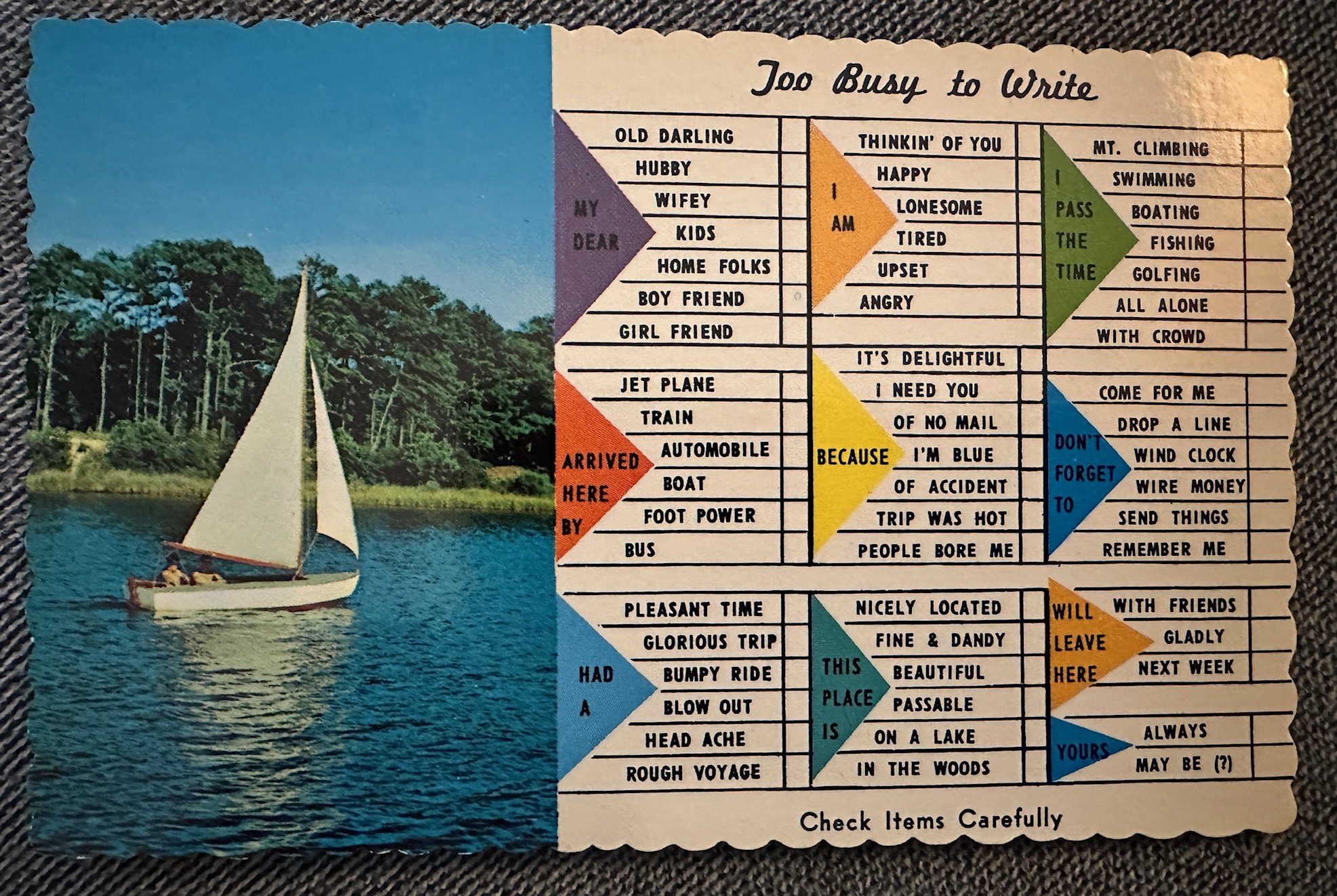

Madoc Hotel c. 1860 Hastings County Historical Society HC-2083

The Constable packed them up and all three headed down to Belleville, with the scythe and shotgun as evidence. It is not clear how the three travelled with one horse. Oddly, on his way back with both Richard and Mary, the Constable chose to stop for a drink at the hotel in Madoc. Time passed before they stepped outside to continue the trip. Right away they realized that some things were missing. While they had dallied inside, the murder weapons, the shotgun and the scythe, had been left outside, unguarded. They were never to be seen again.

When he heard about the case, Father Brennan came at once to the Belleville Jail to do all he could for the Catholic Alywards. His efforts were not just to comfort them, but if he could, to save their lives.

The odds were most assuredly against them. The Judge at the Jury trial was to be William Henry Draper, a man whose credentials appeared impeccable. He had been in an incredible assortment of elected and appointed offices, serving as Attorney General, Prosecutor, Judge and even as the joint Premier of Upper Canada. But by now he was so versed in the law and compelled by its blessed severity that he was beginning to resemble one of those ‘hard hearted Old Testament Prophets’ so feared by all accused and their lawyers.

Judge William Henry Draper

It was not just Draper who foretold of disaster; it was Mary Alyward herself. She simply would not shut up. She told everyone who would listen that she would do it all again. Yet there was still hope that her charge could be reduced to manslaughter, saving her from the scaffold. Perhaps her husband, who had not himself harmed the man who died, could be released entirely.

Despite the loss of the murder weapons, despite the provocations, Judge Draper led the Jury in a righteous quest to convict both of murder. In a rare attempt at clemency the Jury, although they did convict, did so with a ‘strong plea for mercy’.

At this the Judge addressed the sinners and the Jurors sternly on principle.

‘I must tell you that the law allows me no discretion in the matter. I will lay the case before the proper authorities but I deem it my duty to warn you not to spend the short time which outraged humanity yet allows you in the world, in vain hopes and useless endeavours for mercy.’

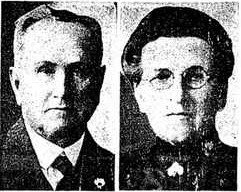

Rev. john brennan

St. Michael's Roman Catholic Church Archives

Both were then told they would be taken ‘to be hanged by the neck until you are dead.’

Richard is said to have yelled, ‘You may hang away, I am not guilty.’ His wife, after for weeks, having confessed to everyone and anyone, now joined in to loudly declare herself, innocent as well.

Poor Father Brennan, along with his nephew, Reverend John Brennan, did his best to petition for them, to comfort them, and to pray with them to the end. He even passed on a questionable claim that Mary should be spared because she was pregnant. All to no avail. Yet he carried on right to the end, praying with them even while kneeling on the scaffolds. When the time came that cold December 8th, 1862, the Belleville public, said to be a crowd of five thousand, little to their credit stuffed themselves into and about the Jail-yard to get a good look at the spectacle of husband and wife hanged together.

For a link to this story on 'Canada’s History” CLICK HERE