1873 Lumber Barons

tHE gAWLEY LUMBER CAMP SHANTYMEN - LOCATION UNKOWN submitted by Sandra Townsend

The greatest business in town was the Pearce Company and its mills. A virtual dynasty had been established by Reeve and Warden, Thomas Peter Pearce. He was nothing if not a consummate businessman. The Pearces built mills at Marmora in 1873 and their resourcefulness would lead them successfully into all sorts of associated businesses for over half a century.

The heart of the Pearce family business was always lumber. Companies before them had logged the vast wilderness north of Marmora, but none had done it so extensively or so well. For decades the family company owned the land and family members dominated local government and society.

In 1897, Thomas Peter Pearce completed an extraordinary purchase. From its nucleus of mills at the Marmora dam, the company expanded to own over 23,000 acres in Hastings County alone.

Since the Ironmaster Charles Hayes lost it to creditors in 1825, the old Marmora Ironworks, (and the empire of forest which fed its furnaces) had gone through a series of less dynamic owners. Now it was the subject of litigation and bankruptcy. By action in the High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, the full holdings were taken from the Cobourg Peterborough and Marmora Railway and Mining Company and offered for sale. For fifty thousand dollars, T.P. Pearce bought the holdings, lock, stock, and barrel.

In addition to the many thousands of acres in Hastings, Peterborough and Northumberland came "all the tolls, revenues, rights, power and privileges" of the railway, "from Cobourg to Harwood and on Rice Lake", "from Rice Lake to Peterborough", "from Peterborough to Chambliss on Chemong Lake" and "from the narrows on the Trent to Blairton".

Add to that, 5 locomotives, 3 passenger coaches, 2 baggage cars, 45 flat cars, 132 ore cars, 5 lorries, a number of train station houses (including Cobourg roundhouse), many shops, one single and thirty-nine double dwelling houses at the mining town of Blairton, donkey pumps, barges and steamboat equipment, furniture, innumerable industrial tools and even "six hundred and ninety tons of iron ore (would not pay to move)", and it is easy to see that this was no ordinary purchase. It was a major transaction and, if managed right, it would be a major coup.

For Pearce, the attraction was the woodlands, waterways and mills. When he sought to sell off parts of the rail lands from Cobourg to Harwood, he dealt so sharply, so astutely, that he nearly stood Cobourg's city fathers on their heads. The citizens of that town met repeatedly in rowdy sessions at Victoria Hall. The line north seemed essential to the growth of Cobourg as a market town. Time and time again they urged their councillors to finalize a purchase of the line to Rice Lake. When they moved to buy it, they never seemed to be able to mail down just what Pearce would accept. A series of frustrated telegraphs issued from Cobourg Town Hall. The northern forester, who seemed so hard to pin down, held all the cards. When Pearce did sell, it was on his terms.

Thomas P. Pearce had three sons, Billie Pearce, H. Reginald Pearce and Frank Pearce.

The latter two would play a part in Village affairs right into the 1930s. Billie became well known and fondly thought of as a Village character until his death in 1933.

From Pearce's Marmora headquarters, a stream of lumberjacks set out northerly each fall. Locals were joined by French-Canadians and even Scandinavian loggers. For three months or more they would work the bush with their axes and crosscut saws. Teamsters would urge on their oxen or, more commonly, their swifter horses. The logs would be trimmed with twelve pound broad-axes, then towed, skidded and cajoled onto the frozen lakes.

As spring thawed the rivers and lakes, the timber would start down the streams and tributaries of the Crowe River and Beaver Creek. "White water men" would jostle the logs, breaking up jams with cant hook, peavey and dynamite.

On Crowe Lake, great rafts were formed. One long time cottager remembers visiting one as a child. There were thousands of logs encircled by chained timber. The central raft had a shed built on it. "There, a family of raftsmen was cooking lunch. On the 'deck' was a wooden capstan to winch the lines holding the ring of logs which encircled the harvest. An old horse waited patiently for the call of duty. A cable, anchor and winch system was used to move log booms across a lake. These anchors have been found in Crowe Lake and Belmont |Lake.

Log boom anchor found in Blairton Bay, crowe Lake by Derek Meridith

Here is an example of an alligator (log boom moving boat) used with a large anchor. These were used on Belmont and many other inland lakes to move log booms. (Courtesy of Wayne VanVolkenburg)

As the logs left the lake, they again had to be urged on, down this time, to the waiting mills at Marmora. Along the river, rock and log platforms were built on the river for drivers to stand on, up to their waists if need be, in icy water. Even today, when the water level drops, those platforms still become visible.

NOTE IN THE BACKGROUND, ST. MATILDA'S CHURCH, CROWE RIVER

Marmora herald , June 27, 1907 " Thompson and Co.;s drive of logs is being taken through here this week. The river drivers have pitched their tents on the west bank of the river near the old Catholic Church."

RIVER GANGS, by Margaret Monk (1967)

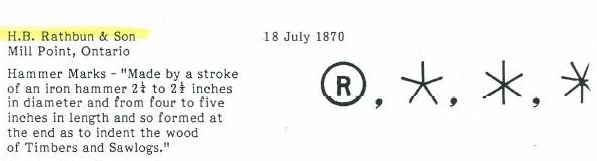

During the river driving days, three companies drove their logs with the same gang of men all on the one drive, with the logs being sorted out just below the iron bridge on Beaver Creek, (recently replaced) about a mile north of the village. This was done according to markings: (Rathburn marked with a "star"; Gilmore with a "G". and Pearce, a "P").

The lumbering industry at that time covered only pine, hemlock, spruce and cedar, as hardwood lumbering did not come into being until later. Hardwood could not be included in the river drive because it would sink, and therefore, portable saw mills were used.

Lumbering was a full year's employment with men going to the bush in October to cut logs, skid them, draw to river or lake. Then as soon as the waters opened, the same men would drive logs to the mills then go into the. mill to help saw them.

The last cook of the Pearce river drive that can be recalled was Bill Rose, father of the late Mrs. Myrtle J ones and Mrs. George Ken. Walking boss was Jacques (Jacob) Wilkes, father of Mrs. Garth Sabine.

Other mills were operated by William Bonter and Sons, owned originally by the family of the late Louis Briggs and continuing to operate until 1925; and Lynch and Ryan who began operations in 1907 and carried on for 20 years in the northern part of the township, and the Coy Mill in Shannick.

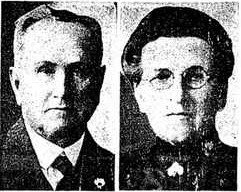

Campion log branding tool. Arlene (Campion) McKee writes: I recall hearing my grandfather, Harry German Campion, having nightmares, dreaming of his riding logs down the river.

Harry German Campion

Just upstream from the dam, the logs were lead into sorting channels. Each was fed into the mill which would seal its fate either as lumber, or firewood. Behind the mills, the great sawdust burner was a country landmark.

It doesn't take much imagination to realize that as the logs and men returned to town, Marmora began to hop. The men had wintered in log shanties dug into the ground, smokey and windowless. Drink was generally prohibited and female company non-existent. As the logs filled up the river, so that "you could walk across without wetting your feet", so the hotels and taverns filled up as well. The men were restless. They had money to spend, and any good entrepreneurs, like the Pearces could help. In any company town, the wages tend to return fairly promptly to the employer.

Thomas P. Pearce Co.

July 7, 1870

Looking north from the west bank of the Crowe River, across the future route of the Trans Canada Highway, you can see the works of thePearce Mill lining the shores all the way up to the dam. Pearce's sawdust burner is the chimney just to the right of the mill. It was described by locals as being "in eruption" when it covered the village in smokey effluent. The extensive stores, mills and other works of the company extend up the bank of the river to the right. At a time when water power was still king, Ontario's industrial enterprises were crowded around rivers, like the Crowe, which had a good flow and a high fall.

The Pearce enterprise itself was located on top of the ruins of Charles Hayes' 1821 Iron Works. A lot of the stone work had been recycled and the site redesigned so that the works were driven by the river's power for a new purpose.

As early as 1893, the Pearce Co. was not only offering all sorts of lumber, rough or finished, but also boasting of the productivity of its Woollen Mill. As it had been during Hayes' days, Marmora was once again essentially a "company town", "The Woollen Mill is equipped with first class machinery, and gives constant employment to fifteen hands. During the past year we have manufactured fifty thousand pounds of wool". The mill sold products to the best wholesalers in Montreal and Toronto, and offered cash or exchange for all the "good clean wool brought to the Mill",

In 1908, the Pearce General Store announced its best year yet. "But", they proclaimed, "ambition knows no rest; one goal reached and another rises in advance". They relentlessly advertised an array of clothing from ladies' corsets to boys' three piece suits with which they gave away a "free genuine watch that would keep time".

Over time, the store became Pearce and Maretts, and later, just Maretts. Although the tradition continued, the ambition that made the Pearce Comany an important enterprise known throughout the Province, inevitably ebbed.

Although its principals continued to enjoy personal prosperity, the company itself declined. The sun was setting on all the old-fashioned lumbering businesses. It was partly that the timberleft was further and further from the mill, partly the advent of forest harvest machineryand partly the arrival of the Great Depression.

On November 30th, 1933, a sad sale of lands was conducted by the County. When the results were tallied, a vast tract of wild lands of Lake Township had been lost by the Pearce Co. to tax arrears. And it had been lost for a pittance. More that 8,000 acres were sold that day. The total proceeds were $1,587.32, a paltry 19 cents an acre. At the same sale, Reginald Pearce himself bought back 1000 acres of company lands for $56.00, which worked out to an even better buy - 5.6 cents an acre.

Style of child's suit sold at Pearce & Marett's

Margaret George , Pete Lucas , Owen Lucas working at Leo Provost Saw Mill . (Photo from Susan Stewart Smith)

For an excellent article in "Country Roads" magazine on the Rathbun Co., Click here.

LOCAL LUMBER COMPANIES: Alex W. Carscallen, Ryan and Lynch, (photos below) Thomas Peter Pearce, Leo Provost, Michael O'Connors, Jack Coy (Shanick), G.B. Airhart Lumber Co., Wells Brothers

NOT SO LOCAL LUMBER COMPANIES: James Cummins, 1862; A.S. Page, Michael O'Brien, H.B. Rathbun & Son Mill Point, Ontario 1870, Rathbun Co., Deseronto, 1885, Gilmour Lumber, Trenton.

In this 1940 photo are Helen Stewart (the girl in the truck who is the daughter of Charles Lummiss), Wallace Lawrence, Charlie Lummiss, Charlie Campion, Harold Landon. taking log to Norwood to make cheese boxes. 1940

Charles Lummiss and daughter Helen, (stewart) c. 1940 photo sent by Vicki Maloney

The Lummiss truck today, north of vansickle Ed Reid Photo

The cheese box

The Ryan-Lynch stave mill, located on the Deer River, behind 1150 Vansickle Rd., Marmora Township

The Barienger brake, or sometimes referred to as a "snubber," was used to ease a heavily loaded log sled down a steep hill.

Ronald Barrons who sent us the above photo wrote: This image shows it (The Barienger brake) hooked to the back of the sleigh. Applying brakes slows the decent of sleigh and in doing so returns the other end of the cable for the next sleigh.

This image is from the logger's museum in Algonquin Park.

Gilmour Freehold now a model forest after early devastation (Enter Domtar) Marmora Herald Feb 1999 By James Fisher

No, this is not about Canadian

hockey skills, but the colourful history, of a private 65,000-acre chunk of the Canadian shield; lumberjacks; and a missing link mystery. The tale begins in the 1830s when the Gilmour brothers logging company of Trenton, Ont., was granted huge acreages in

Eastern Ontario, eventually

reaching up to and into the

present day Algonquin Park.

Over the next 50 years,

every stick ofpine and other

valuable timber north of today's

Highway 7 was systematically

cut down and floated to Trenton. contributing to the construction of

the Trent Canal system and an ingenious uphill log slide from the Algonquin area. For over 50 years, the Gilmour families had absolute control of the economic and social life of the town of Trenton. By 1888, their company employed 600 loggers working year round to feed the appetite of North America's largest and most modern sawmill at the mouth of

the Trent.

Up to 800 were employed in the mill producing lumber, - doors, windows, shutters, cheese boxes, nails. kegs, baskets, lath and pickets. Before the wood ran out, they were annually exporting 19,000 hardwood and pine doors to the U.S. and Europe, as well as 75 Million board feet of lumber.

Littered With Debris

By 1900 the woods were littered with slash and debris that would be covered today. but didn't meet the standards of the time. The

debris became fuel for the major forest fires that seared the land in 1891. 1905 and 1912.

In the early 1850s the

government tried to settle

this desolate area of the Canadian

Shield by building the Hastings settlement road from Belleville to Bancroft.

The road took many years

and dollars to navigate the

ridges and myriad small lakes

and streams left o\er by water diverted by the receding

glaciers. The land was poor, consisting of rocks, swamps and

forest scrub. The Loyalist settlers

found that the pockets of 50-acre Crown grants contained little fertile land; barely enough to grow barley and oats to feed their cattle.

By the turn of the century, there was little sign that settlement had ever taken place. Abandoned

homesteads and hopes were

either incinerated by fire from the leftover logging debris or in the few fertilepockets, grown over by new

forest, or flooded by beaver. To this day, it's difficult to locate the Hastings settlement road, which runs roughly parallel to the present day Highway 62 from Madoc to Bancroft.

By 1900 the land was

owned by the International

Nickel Company for the

mineral leases. They farmed

out the above ground rights

to small sawmill operators

who made packing crates

and ammunition boxes for

the first World War. The

mines were soon spent and

the Central Ontario Railway

from Picton to Bancroft built

to service them, was also

destined to disappear.

Freehold Purchased

In 1956, the Dominion Tar and Chemical Company of Montreal merged with the Howard Smith paper company of Trenton, owner

of 40,000 acres in North Hastings' county, including parts of Marmora, Madoc, Tudor, Lake, Limerick and

Wollaston townships, around the original village of Gilmour. The block became known as the Gilmour Freehold. With deletions, additions and exchanges to consolidate areas, Domtar Forest

Products (the "Gilmour Freehold") now consists of 65,000 acres of rock, swamp and a model forest.

The taxes paid on the Gilmour Freehold go to the local townships and some of the logging roads have opened up the area to recreational uses such as cottages

and deer hunting. Cottage lots for recreation are leased out on several lakes, and the whole

territory is leased to the Limerick

Hunting and Fishing Club and the Madoc Hunt Club, whose individual members hunt an average 100

acres each, with 68 hunt camps maintained throughout the area.

No one else is permitted to hunt on the Gilmour Freehold, and frequent patrolsby the company, club members and the Ministry of

Natural Resources ensure

that only card-carrying members

effectively control the abundant deer population, whose unregulated browsing can destroy valuable seedlings and saplings. They are also able to exercise some control over porcupines,

which eat the tops of mature trees, and rabbits that nibble on bark, killing the young trees.